“A wild place isn’t one unchanged by humans. It’s a place that changes us.”

~Melissa L. Sevigny in Brave the Wild River

Leaves of a backlit aspen glimmer-flutter in low angle sunlight. A robin countersings to the crunch of tires in gravel. The sharp, shadowed edge of Electric Peak contrasts brilliant sky, even at 8 pm. The hummocks beneath Sepulcher multiply in the evening, as each small fold in the landscape casts its own shadow. The air cools quickly as the sun disappears behind the travertine cliff.

This, a moment from the couch on which I’ve spent too many hours the last three days, weathering a cold likely acquired in the overcrowded dining rooms at Old Faithful. Thankfully, it waited to show up until my group of twelve North Carolina educators departed for home.

Twelve people who arrived as strangers and left as friends. Twelve people who put aside their individual desires and experienced the miracle of being in a wild place together. Twelve people who came to experience and learn; twelve people who left changed. And three staff, myself included, who did our best to take care of the details, who laughed and learned alongside the group, and who were changed, too. It is nearly impossible to experience a place like Yellowstone with a group of like-minded explorers, a group where each person has a goal beyond themselves, and not feel the impact. What a privilege it is… even if it ends with a miserably stuffy nose.

I usually have very little time to record the events of Museum trips that I lead, and this one was no different. Years ago I discovered the trick of writing short snippets to help me remember special moments. Of course, I didn’t take much time even for that on this trip. So bear with me as I think back on our nine days in Yellowstone and translate some small glimmers of highlights here…

The golden eagle nest on the rocks at Slough Creek has been there for many years. But I have never seen two adults coming and going multiple times in a row, carrying sticks and conifer branches and leaving them on the nest, the large white chick shuffling to the back to avoid being buried. Dan Hartman says they’re cleaning and fixing up the nest and that this isn’t uncommon. But what a sight to see them return over and over, to watch their golden feathered heads against the blue sky, to see their shadows fly across the rocks.

A black wolf runs across the vivid green along the Lamar River, where the valley is underlain by lake sediments that hold water, limiting the growth of trees and instead supporting lush meadows. A small creek hugs the raised terrace nearer to the road, far from the river. The dark coat of the wolf reflects in the glassy water as it jumps in and swims the short distance before disappearing behind a hill.

An overnight storm that carried snow to higher elevations leaves lingering low clouds hugging the slopes of Mount Washburn in the early morning. I’m thankful that the Park Service didn’t see the need to close the mountain pass, because this is the most beautiful I have ever seen it. Hints of pines and firs are dark enough to appear through the thin mist. Where cloud breaks, the fresh green meadows gleam. In the foreground, wet snow clings to the towers of silvery lupine blooms. Beyond, sun glints on the snow-covered slopes and disappears into the black volcanic rocks, a study in contrast. This snow is perfect packing snow, making excellent snowballs and tiny snowmen. It tastes fresh and crunchy, like childhood.

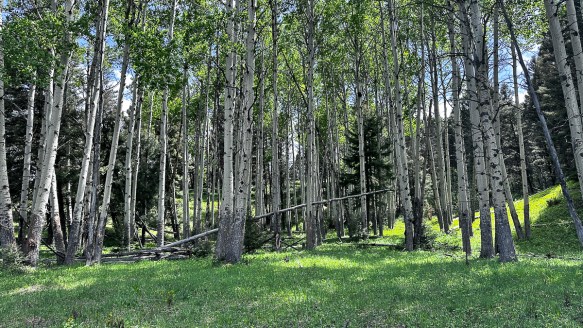

Dan Hartman takes us to his beloved aspen grove and teaches the group to wait and watch the nest cavity until the hairy woodpecker brings a mouthful of ants to the nest and the excited babies chorus inside. As we climb the hill beyond, for perhaps the first time (though I’ve tried many times before), I find a nest of my own, tucked in the crotch of an aspen tree. Days later and far from Dan’s grove, the group finds another hairy nest and stands by the trail waiting for a feeding, just as instructed.

At West Thumb Geyser Basin, where hot spring runoff cascades under the boardwalk trail, we examine the temperature and color patterns with an infrared thermometer. In my minds eye, and perhaps in a future nature journal or activity, I create a graph that maps the relationship between the two. As orange shifts to yellow to cream, temperature rises from 70 degrees to 135. Of course, the 170+ degrees of the spring itself is not so close, but we measure it from a distance are share our amazement with nearby visitors.

Snow is falling in Hayden Valley and its freezing cold. Two while pelicans, perhaps juveniles, as they have some black on their heads, dip in unison as they sink their bills into the creek in search of food. They repeat this dance multiple times. It is entrancing. Entrancing enough, in fact, that I miss seeing a gray wolf cross the road in front of my van!

I spot a black dot up the hill beyond a parking area where the Pebble Creek Campground used to be, before the 2022 floods. It’s so dark it must be a black bear. It moves into the trees as we walk up the old campground road. I don’t think we’ll see it again, but Greg persists and soon waves us toward him. From a new angle, we watch the bear feeding on lush grass while her two cubs, one black colored and one cinnamon, play in the tall grass. A multi-generational family of women joins us, the younger helping the elder cross the rocky ground. I help them with their scope, and they are thrilled to watch the bears.

At dawn in the Upper Geyser Basin, I see four people standing in front of Beehive Geyser, my favorite. One wears a blanket wrapped around his shoulders. Another carries a stadium seat. All wear hats. This is a good sign. Beehive is not a “predictable” geyser, erupting once every 12 or 15 or 17 or 24 hours, depending on its mood (or the vagaries of the groundwater and heat beneath the surface). But the behavior of the people who love geysers, and who have studied long enough to see patterns where no one else does, is much more predictable. As we approach, water splashes out of Beehive’s cone to a height of maybe 10 feet. Another good sign. Sure enough, within another 5 minutes, a small crevice between the geyser cone and boardwalk fills with water and then erupts, spraying about 8 to 10 feet into the air, angled toward the boardwalk: Beehive’s Indicator. Twenty minutes later (hence the name “Indicator”), steam and water burst from Beehive Geyser to a height of 200 feet. The geyser is only about 30 feet from us. It is illuminated by the rising sun behind us and soon a double rainbow appears in the spray and steam. One of the Geyser Gazers says this is the most beautiful eruption of Beehive he has ever witnessed. It is likely he has witnessed many.

This group really loves moose. It seems they want to see a moose more than a wolf or a grizzly. Our first sighting is a bit disappointing: at a distance and brief. Our second is pretty stellar: a young bull is close in a creek feeding the Snake River, repeatedly blowing bubbles out of its nostrils as it dips its head into the shallow water to feed on vegetation. Our third… unexpected and stellar! Two large bull moose are along Soda Butte Creek. But rather than disappearing in the willows, they turn and move toward the road. An animal whose shoulder is at least 7 feet tall doesn’t get hidden in the sagebrush the way a coyote does! So we watch their progress across the valley with the iconic landmark of Soda Butte Cone in the background. They cross the road at a safe distance between our cars and others down the road; thankfully, no one sees the need to approach closer. But that’s not all! They turn and face each other, one rears on its hind legs, ears flat to its head; the other moves off more quickly. They turn and face again, looking like they might lock velvet-covered antlers, an unexpected behavior at this time of year. They move uphill into the trees and feed. What a sight!

We spend quiet time at the Laurance S. Rockefeller Preserve in Grand Teton National Park. It is my favorite visitor center. It feels like a sacred space, set aside to celebrate the connection of humans to nature. Phrases of a poem by Terry Tempest Williams, commissioned specifically for this place, lead visitors through a multi-sensory exploration of the Tetons. A line catches my eye: “We recognize the soul of the land as our own.” In the quiet moments that follow, I take time with my journal to reflect on that theme. Here are my thoughts…

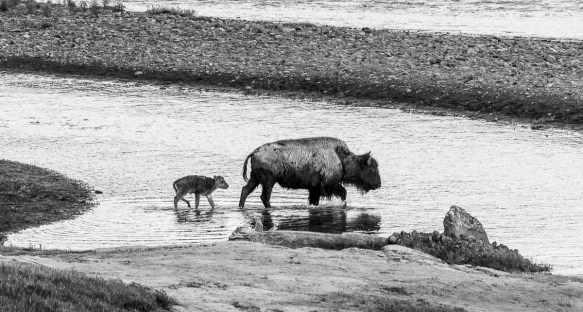

The soul of the land is wild. It is that which draws us into wilderness, and life. It is the harvester ants gathering honeydew from the dark green aphids on the stem of arrowleaf balsamroot. It is the joyful song of the yellow warbler in the willow thicket. It is the chatter of the creek of rounded riverrocks. The cirque scooped into stone by ice. The croak of the raven looking for a meal. It is the fragile bark of the aspen marked by a bear’s claw. It is the cloak of steam disguising the landscape at dawn. It is the bison herd moving as a river down the valley.

This land resonates within me. It compels me to stillness, to being. Also to movement, to wonder. It transforms complacency to curiosity, cynicism to joy. I am not the key. I am irrelevant. But I alone can build a connection. I alone can allow my soul to be animated by this land. I alone can permit my transformation. I alone can recognize the soul of the land as my own.

We walk down a trail paralleling Glen Creek through an open sagebrush meadow rimmed with angular mountain peaks. As we lose sight of the road, we turn off behind a grove of lodgepole pine and Douglas fir. The hill flattens its slope before climbing further towards Terrace Mountain. We collapse in the grass and form a circle. I kick off my sandals, dusty from the well-worn stock trail, and feel the rough blades of grass beneath my feet. We talk about things that we will take home with us when we leave tomorrow. Not physical things, of course, as collecting anything in a national park is prohibited (with 5 million visitors, nothing would last, even rocks). Nonetheless, each of us will carry something. New knowledge and ideas. New stories to share with friends, family, and students. New intentions. Renewed passion. Perhaps what means the most to me is this: a new connection to this place and to each other. To hear those words spoken from the group, to see the nods of agreement, to feel their truth inside myself… this is why my work is a privilege. This is why it is important. I am grateful.